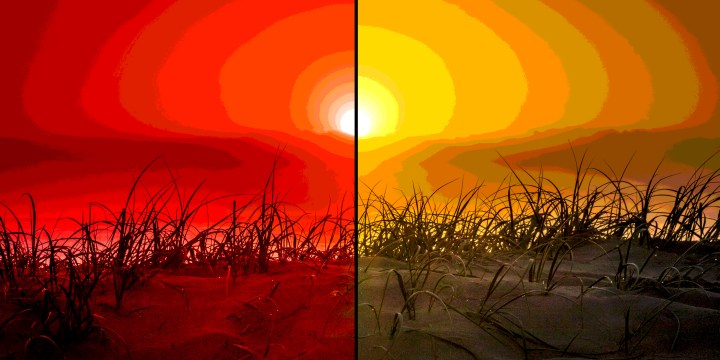

Our Burning Planet

Superfreak pivot: When climate engineering came to South Africa

Cooling the earth by blocking out the sun, although potentially disastrous, is now a real answer to climate change. As a Harvard research paper published late last year proved, solar geo-engineering is both technically feasible and relatively cheap. With governments and international bodies considering the technology, a South African university has just announced a study. But how convenient is this answer for our politicians and heavy emitters?

I. Global Hollywood

In his book The Planet Remade: How Geo-engineering Could Change the World, Oliver Morton laid down a potential scenario from the not-too-distant future. As briefings editor at The Economist and former chief news and features editor at the scientific journal Nature, it was a given that this scenario—a thought experiment on the deployment into the stratosphere of “climate engineering” aerosols—would be based more in science fact than science fiction. Which is exactly what made it, like the best work of Robert Heinlein or Charlie Brooker, truly terrifying.

According to a Harvard study published in November 2018, three years after the release of Morton’s book, it would work in practice like this: a fleet of purpose-built aircraft, with disproportionately large wings relative to their fuselages, so as to allow “level flight at an altitude of 20 kilometres while carrying a 25-ton payload,” would inject 0.2 million tons of sulphur dioxide into the lower stratosphere per year—thereby reflecting enough solar radiation back out into space to cut the rate of global warming progressively in half. Pre-launch costs in 2018 values would come in at $3.5 billion, with yearly operating costs at $2.25 billion. Given that in 2017 around 50 nations had military budgets of $3 billion or more, noted the Harvard scientists, the barriers to entry would be remarkably low.

“It is not a large nation that does it—indeed, it is not a single nation’s action at all,” speculated Morton back in 2015. “Sometime in the 2020s, there is a small group of them, two of which are in a position to host the runways. They call themselves the Concert; once they go public, others call them the Affront. None of them is a rich nation, but nor are they among the least developed. All of them already have low carbon-dioxide emissions, and all of them are on pathways to no emissions at all. In climate terms, they look like the good guys. But their low emissions and the esteem of the environmentally conscious part of the international community are doing nothing to reduce the climate-related risks their citizens face.”

So why “truly terrifying”?

Because, as Morton went on to explain, solar geo-engineering—otherwise known as solar radiation management, or SRM—was not (or at least was no longer) a conceptual absurdity. When he wrote his book, its probability of deployment was already based on two of the most urgent existential questions in the history of humanity: 1) Are the risks of climate change great enough to warrant serious action aimed at mitigating them? 2) Will the world’s largest industrial economies be able to lower their carbon emissions to net zero by the middle of the century?

But terrifying more specifically because, by 2018, the answer to the first question was a scientifically unqualified “yes” and to the second a statistically implausible “no”—and yet the effect of SRM on the biosphere was still unknown. With the results from the Harvard study leading to the scheduling of tests as early as the first half of 2019, the Berlin-based climate science and policy institute Climate Analytics wasted no time in recommending a global ban on the technology.

“Solar radiation management aims at limiting temperature increase by deflecting sunlight, mostly through injection of particles into the atmosphere,” the institute noted. “At best, SRM would mask warming temporarily, but more fundamentally is itself a potentially dangerous interference with the climate system.”

SRM, argued the scientists at Climate Analytics, would “alter the global hydrological cycle as well as fundamentally affect global circulation patterns such as monsoons.” It would not “halt, reverse or address in any other way the profound and dangerous problem of ocean acidification which threatens coral reefs and marine life as it does not reduce CO2 emissions and hence influence atmospheric C02 concentration.” Also, the scientists pointed out, the approach was “unlikely to attenuate the effects of global warming on global agricultural production” as its “potentially positive effect due to cooling” was projected to be counterbalanced by “negative effects on crop production of reducing solar radiation at the earth’s surface.”

In other words, according to Climate Analytics, while cooler temperatures would be helpful to the world’s farmers, the crops would still need sunlight to grow. And none of the above even counted as the number one reason that the institute was raising the alarm—SRM’s gravest danger, these scientists and policy experts insisted, was that it would divert attention from the core problem, which remained the unprecedented amount of carbon being spewed daily into the atmosphere by the extraction of coal, crude oil and natural gas.

For Morton, this was the predicament known as the “superfreak pivot”—the turning of large masses of humanity from the position that “global warming requires no emissions reduction because it isn’t a real problem” to the position that “the Concert has it all covered”. It was a predicament highlighted too by Harvard scientist David Keith, who told the Guardian in 2017:

“One of the main concerns I and everyone involved in this have is that Trump might tweet ‘geoengineering solves everything—we don’t have to bother about emissions.’ That would break the slow-moving agreement among many environmental groups that sound research in this field makes sense.”

As for South Africa, less than two months after publication of the seminal Harvard paper of late 2018, a press release was issued by the African Climate and Development Initiative of the University of Cape Town.

“UCT researchers to embark on pioneering study on potential impacts of solar geoengineering in southern Africa,” it stated.

II. Local Hollywood

As the recipient of a grant from the international DECIMALS Fund (Developing Country Impacts Modelling Analysis for SRM), the UCT team cited two reasons for going ahead with the study—and both of them had to do with the social and economic havoc that anthropogenic climate change had so far wrought in our corner of the world. First, the 2015/16 summer rainfall failure over southern Africa, which led to 30 million people becoming food insecure in South Africa, Mozambique, Botswana and Zimbabwe. Second, Cape Town almost running out of water in 2018. If SRM could be done in a safe and reliable manner, so the rationale went, it was “the only known way” to quickly offset the temperature increases that were behind the droughts.

“We want to understand the impact of solar radiation management on drought conditions,” Dr Romaric Odoulami, the project’s leader, told Daily Maverick, “that’s our motivation. What will the implications be for regional agriculture? But I want to make one thing clear: SRM has never been implemented in the real world… and we are not going to do it either.”

What the African Climate and Development Initiative was going to do, said Odoulami, was climate modelling. The project, he added, would run for the next “one or two years”—as soon as he got “something interesting,” he promised, he would let Daily Maverick know. For the moment, he wanted to leave us with this:

“Solar radiation management doesn’t stop climate change. It doesn’t stop global emissions of greenhouse gases. The only thing it does is help to reduce the global temperature by reducing the amount of solar radiation reaching the earth’s surface.”

This caution in the face of the sheer unprecedented scale of the thing was also detectable in the words of Andy Parker, project director of the Solar Radiation Management Governance Initiative, the UK-based organisation—founded in 2010 by, among others, The World Academy of Sciences and the Royal Society—that set up the DECIMALS Fund in 2018. Speaking to Daily Maverick from a conference in Bangladesh, Parker was vague yet morbidly fascinating on the legislative context that could eventually give the green light to SRM.

“That’s really tricky to predict,” he said. “We can imagine various different deployment scenarios. There’s the desperation scenario, where a country or perhaps a coalition of countries that are really suffering from climate change decide that they are going to use solar geo-engineering to stop the temperature from rising. That could be seen as unilateral and illegitimate deployment. At the other end of things, it’s possible that through the United Nations—the UN General Assembly or one of the UN conventions—there’s a much broader coalition that comes together with much more legitimacy to develop a decision-making infrastructure for if we were to ever use this, or indeed, for how we would reject it.

“Really, at this stage, we don’t know what’s going to happen. We don’t know what’s going to happen with the research, we don’t know how governments are going to deal with this, and we don’t know how quickly and how deeply the impacts of climate change are going to bite.”

In South Africa, unfortunately, all indications are that the bite is going to be serious. As Daily Maverick learned from the country’s leading land-based climate scientist in October last year, we are warming at twice the global average. At 3°C of global warming, which is 6°C regionally—and which at current emission rates we are steaming towards, as per the most conservative estimates, before the end of the century—there will be a total collapse of the maize crop and livestock industry. This is something that the Department of Environmental Affairs seems to understand well, as evidenced by their “Third National Communication” under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, submitted in March 2018.

But the other unknown factor in this general SRM universe of “unknown unknowns” is the person that currently sits atop the DEA. Has Nomvula Mokonyane, who was named at the State Capture inquiry on Monday for allegedly accepting bribes in the form of monthly cash payments, even read the Third National Communication? Does President Cyril Ramaphosa plan on replacing her with someone who will? Aside from Tito Mboweni at treasury, does anyone in the upper echelons of the ANC get the urgency of the situation?

These are the questions that highlight the possibility of South Africa one day performing the superfreak pivot. Because it might not only suit the government to defer to technology when the food and water shortages get real, it might also suit Sasol, the coal mining companies and the country’s heavy emitters at large. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider