#ANCdecides2017, South Africa

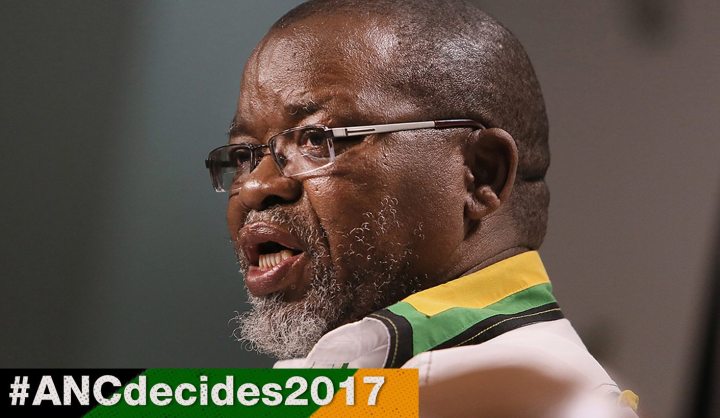

Analysis: In the centre of the ANC’s gravity field – Gwede Mantashe

Amid the turmoil around the ANC’s national conference, definite predictions are few and far between. But one thing can be said with absolute confidence: at the end of it, Gwede Mantashe will no longer be secretary-general. He has indicated that he will refuse to stay in the position any longer. He has been at the centre of the ANC for a decade. It has been arguably the most damaging decade for the party, a decade of going sometimes so wayward, it may not even survive. And yet, it is hard to blame Mantashe himself, even as many of his critics will try. But Mantashe has also been something else for 10 years: he has been the centre ground of politics, the centre of gravity, the man right in the middle of the spectrum of a country where politics goes from nationalist right all the way to Stalinist Left. To examine the last decade is sometimes same as examining Mantashe. By STEPHEN GROOTES.

When I mention the name “Gwede Mantashe” to people who are not political, and not journalists, I’m often struck by the anger it evokes. To “Mantash” has become a verb, meaning to “to backtrack” or reverse your position. He is often seen as the man defending the indefensible. Or, if you prefer, he is the man who has most publicly defended the actions of President Jacob Zuma.

For those who cannot understand how and why he has done this, this has earned Mantashe a central place in Hell. To them, what he has done is evil: placing of Zuma and the ANC above the country.

For many journalists who have known Mantashe throughout his tenure, it is much, much more complicated than that.

He is approachable, interesting, and always funny. Once, just a few months after Julius Malema evicted Jonah Fisher from a press conference, another reporter got into a heated spat with then ANC spokesperson, Jackson Mthembu. The two were going at each other in full view of a fascinated press pack. Mantashe defused things with the simple chirp to the reporter, “Don’t worry, no matter what happens I won’t throw you out.” The laughter ended the tension immediately.

Then there is the fact that he likes to make jokes at others’ expense, but will also take it in return.

For a long period he was also the chair of the SACP. When this reporter first started working for this publication, and while still working for EWN, Mantashe demanded to know which was my real employer, Daily Maverick or EWN. Taking my life in my hands, I retorted that I was not the only person in the room with two positions. As I said it he couldn’t control his response, breaking into laughter. Considering the relative power positions, and the fact that many people at the time thought he was the most powerful person in the country, it was a gracious, human response.

To know Mantashe is also to know a person who is genuinely interested in people; he seems to enjoy other human beings more than almost anyone else in his circles. Most politicians will avoid journalists if they can. Not Mantashe; he seeks us out. In Cape Town, while hiring a car at the airport, he breezily wandered up to the counter where I was getting mine, to greet and cause general consternation. He’d spotted me from afar and come to say hello. Later, at Parliament, I was trying to interview the then leader of the DA, Helen Zille. He came up to her and gave her a huge hug. It was both warm and political. There was something very human and uniquely South African in that moment. As well as it being an expression of political power.

Perhaps it is his love of argument, the fact that to him, speaking and debating is as water to a fish. He couldn’t live without it. Along with that is his ability to understand and depersonalise debates. He may lecture you, but he won’t lecture your identity. Not many of his current comrades subscribe to the same.

Many journalists also have stories about how he has phoned to remonstrate about their reporting. One, who worked for a weekly paper, was told that they would have a telephone appointment at the same time on the day of that paper’s publication. In some cases, this has been difficult to deal with, in others, it has been more of a friendly conversation.

But Mantashe’s decade of running the ANC is not going to be remembered for his jokes, or his whistling or his press conferences. It is going to be remembered for the political actions that he took part in, and for the era in which he played a leading role, at times the leading role.

It may be ancient history, but he came into office in the middle of the ANC’s first major crisis. He was on the slate that defeated Thabo Mbeki at Polokwane. In holding a contested leadership election, the party had done something it had never done before while in power. Eight months later, he was part of a two-person delegation who had the task of informing Mbeki that the National Executive Committee was recalling him. It took several months, and much anger, but eventually Mosiuoa Lekota served his divorce papers on the ANC and launched Cope. The party is a joke now, and Lekota had to eat his hat at the last elections. But at the time it most certainly was not. There were real fears Lekota could get custody of a third of the ANC in the divorce. Mantashe’s management of the situation must have had much to do with how it ended. What threatened to become a split became only a splinter, much to the disappointment of the urban middle classes, who were already beginning to tire of Zuma.

Then again, his biggest accomplishment might only have been to delay the split by nine years or so.

By this stage of 2009, the ANC was limping from crisis to crisis. Cope was gone, but Julius Malema was undergoing his Damascene conversion – from once threatening to “Kill for Zuma” to claiming he had “turned the ANC from a democracy into a dictatorship”. The strategy, which Mantashe was clearly a part of, was to draw out the crisis. The longer it was prolonged, the longer the endless disciplinary hearings went on for, the harder it was for Malema to maintain the outrage and his followers’ excitement.

By the time the long process was all over, Malema had lost momentum and his ANC career was over.

It took time for him to regroup and get the Economic Freedom Fighters off the ground. By that time, in 2013, the main political issue was corruption, and Zuma’s place in it.

As the National Executive Committee (NEC) continued to bat away the claims against Zuma, Mantashe seemed to get more and more exasperated at having to answer questions about Nkandla.

The climax to that dynamic came on a Friday night in April 2016, after the Constitutional Court had found that Zuma and Parliament were in breach of the Constitution for ignoring the findings of the Public Protector. Zuma addressed the nation, which hoped he would resign, and spectacularly failed to do so.

Mantashe was doomed to hold a press conference at Luthuli House immediately afterwards. I couldn’t make myself go. Watching a man debase himself by defending the indefensible is not pleasant, especially when it is someone that you respect.

Nkandla may have been a public turning point for Mantashe, but his real turning point was probably five months before that wretched press conference: NeneGate.

It can sometimes be forgotten that Mantashe is officially in charge of communication for the ANC. The party’s statement “recognising and noting”, but not congratulating, Des van Rooyen on his appointment as Finance Minister in 9 December 2015 showed that Luthuli House was deeply worried. It set the scene for what was to follow, the reappointment of Pravin Gordhan and everything that flowed from it.

Looking back now, it was that moment that divided the ANC beyond repair. It was suddenly clear that the ANC had lost control of Zuma, and by the ANC, I meant Mantashe.

From then on, things were never the same. Their relationship had changed fundamentally. This became more and more obvious around Gordhan, who was charged with fraud, while the Mantashe-controlled ANC machine appeared to show its support for him. It was obvious he himself supported Gordhan. At the time, some members of the ANC, including people like Derek Hanekom, were publicly saying they would go to court to support Gordhan, while others, like Kebby Maphatsoe, were beginning to make opposite claims about him.

It was obvious that what started as the NeneGate earthquake would end up in the tectonic plate shifts over Gordhan.

The political earth in the movement shattered the night Zuma fired Gordhan at the end of March 2017. The ANC’s top six were split asunder, the national working committee criticised Zuma, the NEC spent days discussing recalling him. Mantashe claimed the new Cabinet was a list created not in the ANC “but elsewhere”. He joined Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa and Treasurer Zweli Mkhize in publicly criticising Gordhan’s removal.

It was also surely Mantashe who played a key role in the appointment of Jackson Mthembu as Chief Whip of the ANC. When the history of this period is written, this will be seen a key moment. Mthembu was able to use this position to first get ANC MPs to remove Hlaudi Motsoeneng from the SABC, and then take the first steps towards fixing the public broadcaster, a direct threat to parts of Zuma’s empire. Then, even worse for Zuma, came the inquiry into Eskom. It is impossible to think that any of this could have happened without Mantashe. Mthembu would have needed his support and his political backing to get it moving.

That doesn’t mean that Mantashe comes out blameless. In public, he can be exasperating. When Police Minister Nathi Nhleko appointed Berning Ntlemeza as an acting head of the Hawks, after a judge had found him to be “without integrity… and honour” and to have lied under oath, Mantashe refused to comment. I had an incredibly frustrating and difficult question and answer session on live TV over this. His defence, that the ANC could not comment on a government appointment, was hogwash, and he knew it. After our tussle, another journalist, a regular at Luthuli House, messaged to say that it had been cathartic to watch, because they were also so frustrated with the ANC. It was one of those messages that made me realise so many other people felt the same.

And if he had spoken, perhaps Ntlemeza would have been removed earlier. Perhaps not, but we’ll never know.

This is probably the main problem with Mantashe’s legacy. There were many things that he could have done something about, but didn’t. Nkandla, the Waterkloof landing, the corruption charges, the wholesale destruction of the SoEs. the Guptas. the Guptas. the Guptas. Perhaps, ultimately, the fact that he helped get Zuma elected leader of the ANC in the first place. This is why so many people are frustrated with him. At each point he seems to have put the ANC and its “unity” ahead of the needs of the country. Earlier this year, when the ANC caucus was meeting ahead of a confidence vote in Zuma, it was reported that he said those who wanted Zuma out could wait until December and do it without splitting the party.

It was Mantashe’s situation summed up neatly. The party is more important. Despite the fact that the country is bleeding billions of rand and hundreds of thousands of jobs every quarter.

In recent days, those who support Zuma’s opponents have taken serious issue with people like Social Development Minister Bathabile Dlamini, for rants against the courts. She is extremely critical of the judges in the ruling around the appointment of a National Director of Public Prosecutions, saying the “judiciary carries itself as if it’s being lobbied”. Many see this almost as a threat. But Mantashe has perhaps actually gone further then her. During the incredibly difficult time of the turmoil over The Spear image (of a naked Zuma, exposing himself while wearing a coat in the style of Lenin), Mantashe told the ANC’s members massed for a march, “We will not win in court what we have not won in the streets.”

He has a track record of comments like this. In 2008, he accused Constitutional Court judges of being “counter-revolutionary”, a comment that sparked Zapiro’s famous Rape of Lady Justice cartoon.

Despite all of this, Mantashe could well rescue his legacy this week. It is obvious that he is campaigning against Zuma, and therefore against Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma. His comments and tweets (yes, someone else, someone younger, does the actual tweeting for him) that “there will be a crisis in the ANC” if the deputy does not follow on from the president, have made this crystal clear. In many ways, he has led the fightback against Zuma. He protected Mthembu after he publicly spoke against the removal of Gordhan, who seemed to curb the worst excesses of Zuma and the Guptas. He must have been very important around the time that Van Rooyen was removed and Gordhan re-appointed to the Treasury.

All these issues will most likely culminate in the next few days. If his chosen candidate, the current deputy president, wins, he will be on his slate as Chairperson of the ANC. He will be seen as the man who led a revolution against Zuma from the front. And he will also be seen as the person who controlled the architecture of the ANC, who protected it, to ensure a democratic outcome for ANC delegates when they vote. But if Ramaphosa loses, and Mantashe with him, many people, particularly in urban areas, may feel that he had it coming. That he could have done more, earlier. That he allowed his love of the ANC, of the movement, of his comrades, to come before what duty he may have had to the nation.

Through the last decade it has been Mantashe’s job to the keep factions in the ANC roughly on the same page. It is impossible. Things have moved too far, too fast, the factions are too far apart. It is hard to think of anyone who could have managed the party over the last decade better than he. Certainly, if Dlamini Zuma wins, Mantashe could well watch Ace Magashule in the job with some satisfaction.

But in person, almost no matter what happens, Mantashe is bound to keep that sense of cheerful optimism, that unrestrained joy in chancing upon someone he knows, the simple fun of jokes and comments and debates and arguments. It is his water, and sometimes, there is enjoyment in watching a fish swim. DM

Photo: ANC Secretery-General Gwede Mantashe addresses the media at a briefing following calls for President Zuma to step down, in Johannesburg, South Africa, 05 April 2017. EPA/STR

Become an Insider

Become an Insider