South Africa

The 2017 Child Gauge: How we can turn around R300bn in damage to SA’s children

The annual South African Child Gauge has been released, and the results were not surprising: our children are in trouble. But as State Capture becomes an increasingly familiar part of our national vocabulary, and the budget for tertiary education dominates headlines, one wonders: where is the money going to come from to take care of the next generation? By MARELISE VAN DER MERWE.

South Africa needs to invest in more nurturing caregiver networks if it is to mitigate the damage being done to children by violence, poverty and inequality – damage that costs the economy over R300-billion per year.

This is according to the 2017 South African Child Gauge, the 12th annual report of its kind, released on Tuesday 28 November.

The report broke down recommendations into five key areas to prioritise if children are to thrive. These were responsive care, child nutrition, violence prevention, reading, and inclusive services.

Published by the University of Cape Town Children’s Institute, alongside UNICEF South Africa; the DG Murray Trust; the DST-NRF Centre for Excellence in Human Development, University of the Witwatersrand; the Standard Bank Tutuwa Community Foundation, and the Programme to Support Pro-poor Policy Development in the Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation, the Child Gauge is a review of the latest research on a particular theme. This year’s theme is “Survive, Thrive, Transform”, and examines what it will take to allow South Africa’s children to thrive.

The good news: Since 1994, poverty has decreased, and children’s survival and access to basic services has improved. According to keynote speaker at the launch, Minister in the Presidency Jeff Radebe, a greater percentage of children now live in a formal housing environment, and the well-being of children is a priority leading up to 2030.

Many of the improvements have been at policy level. A report by Unicef and the South African Human Rights Commission, for instance, found that between 1994 and 2011, progressive legislation, reorganisation of administrative systems and, most important, the introduction of a Child Support Grant had had a significant impact on children’s quality of life. So, too, had the treatment of HIV-infected infants at government-run health facilities and more widespread access to schools.

The bad news: despite improvements, it’s not enough.

The quality of education, the number of child-headed households*, exposure to violence and the impact of inequality on the provision of basic services and human rights remain major concerns. The worse news: tackling it will be a Herculean task spanning multiple sectors.

Radebe pointed out the developmental damage that exposure to environmental stresses could do. UCT echoed this. “Violence, poverty, hunger and poor quality education continue to compromise children’s development and life chances, with a negative impact on the country’s development [overall],” the university said in a statement.

“Most of South Africa’s children are surviving, but too many are failing to thrive and achieve their full potential, and this is costing the economy billions in lost human potential,” it added. “Investing in children – and particularly in violence prevention, networks of care, nutrition, education and inclusive services – would drive the next wave of social and economic transformation, boost gross domestic product, and secure a more sustainable future for everyone.”

The failure to take care of the next generation is bad news for the economy. In perspective:

- A recent study found violence against children cost South Africa an estimated R239-billion – or 6% of the GDP – in 2015.

- Stunting – a sign of chronic malnutrition that affects one in four children under five in the country – compromises children’s education, long-term health and employment prospects, and costs the country an estimated R62-billion per year. The best predictor of children’s economic potential as an adult is their height at two years old.

- The first 1,000 days of a child’s life are critical in determining his or her future development, productivity and economic contribution, and the economic returns on investing in this period of a child’s life are highest. Notably, children who fall behind at this stage tend not to catch up. Yet in South Africa, the lion’s share of education investment is in tertiary education.

- Two-thirds of the country’s children live below the poverty line.

- More than 5.5-million children go hungry.

- Just 35% of SA’s children live with both their parents and 3% with their fathers – absent fathers are a significant problem.

- Many children still enter Grade R without having had access to ECD (Early Childhood Development) programmes.

- Many learners in South Africa are behind global averages on reading and arithmetic skills.

For children, the consequences of these issues can be lifelong. According to the researchers, “Frequent or ongoing harmful experiences of poverty can fundamentally change early brain development and lead to negative outcomes such as aggressive and antisocial behaviour across the life course – from bullying on the playground to violent and unstable adult relationships.”

The researchers say the report’s theme was chosen to align with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), because – in the words of Hervé Ludovic de Lys, UNICEF South Africa Country Representative – a new approach to human development should “start with the most vulnerable”.

Lucy Jamieson, CI Senior Researcher and lead editor of the SA Child Gauge 2017, said the SDGs could impact on South Africa “provided we start by investing in children”.

Which is all very well and good. But what, in practice, does this mean?

The practicalities

Given budgetary restraints, UCT called the report “a call to action” to prioritise responsive care, child nutrition, violence prevention, reading and inclusive services. It was important to build on “what is working”, the statement added.

Prof Benyam Dawit Mezmur, Chair of the African Union Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, argued for the use of a) evidence-based programmes and b) starting with those who were hardest to reach first. This, he said, would both be cost-effective and speed up access to services. But solutions will still not come cheap.

Linda Richter, Distinguished Professor and Director of the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Human Development at the University of the Witwatersrand, emphasised good nutrition, protection from disease, violence and stress; and opportunities to learn. “These elements are interdependent and mutually reinforcing, and are essential to prepare them for adulthood,” she said.

In practical terms, this means Albus Dumbledore was not far off: the first and most important cushion against childhood adversity is a nurturing network, and the capacity to absorb it. “The presence of nurturing and responsive caregivers … can make an enormous difference to enable children to reach their full potential, help break the cycle of violence and protect them from the adverse effects of poverty,” the UCT statement said. This cushion begins at home, but also extends to social support within schools and the broader community.

Nurturing young children’s capabilities, added David Harrison, Chief Executive Officer of the DG Murray Trust, can improve the chances of employment; promote economic growth, and create a safer, happier society. Nurturing children’s growth and development from conception to adulthood helps unlock their potential and can, if not eradicate inequality, at least mitigate some of its effects.

The report highlighted concrete steps that could be taken to build such networks.

Caring relationships

At the moment, many caregivers’ capacity to nurture is impacted by violence, poverty, social isolation or the high incidence of mental health disorders in South Africa. Lizette Berry, CI Senior Researcher and co-editor, says the level of responsive care given to children and adolescents impacts on their confidence, motivation and ability to form healthy relationships. Access to services, social support and healthcare for adults therefore benefits children. The report recommends family support, parenting programmes, community-based services and practical support such as maternity leave, childcare facilities, the promotion of parent-friendly working environments, and social assistance.

Violence prevention

South Africa has a very high level of crime and violence. CI Director Professor Shanaaz Mathews says the exposure of children to abuse, neglect and other forms of violence perpetuates this cycle, increasing their risk of mental health disorders and substance abuse. The body of research on violence prevention in South Africa is increasing, however, she says – which is slowly helping to design “multisectoral prevention strategies that have been proven to work”. In the meantime, support offered remains woefully inadequate: state-sponsored facilities for sexual violence survivors, for instance, are not functioning adequately; there is a shortage of social workers, and police are facing job cuts.

Improving nutrition

Stunting remains a perennial problem, affecting more than a quarter of children under five and costing the economy a staggering R40-billion annually. Research released in 2016 found that South African children were worse off than their counterparts in many poorer countries, including Haiti, Senegal, Thailand, Libya and Mauritania. Unfortunately, stunting is a reliable predictor of a child’s long-term economic potential, meaning many of SA’s children have a lot of catching up to do. David Sanders, Emeritus Professor and Founding Director of the School of Public Health at the University of the Western Cape, says investment in a stronger team of community health workers will help, extending healthcare to vulnerable households and promoting breastfeeding. Daily Maverick previously reported that the Zero Stunting Campaign is calling for changes to administration of the childcare grant, so that nursing mothers can access funds earlier.

Zanele Twala, Chief Executive Officer of the Standard Bank Tutuwa Community Foundation, called for children to receive both early stimulation and nutritional supplements.

Literacy and numeracy programmes

A 2011 study revealed that almost 60% of learners could not read fluently, or fully understand what they were reading, by the end of Grade 4. Dr Nic Spaull, Senior Research Fellow at the Research on Socio-Economic Policy group at Stellenbosch University, says children need access to books; teachers require training, feedback and support (especially following curriculum changes), and reading should become a daily routine, inside and outside the classroom.

Focusing on inclusivity

Children with disabilities are, too often, left behind. Dr Sue Philpott, who previously spoke to Daily Maverick, says the links between families, non-profit organisations and government must be strengthened in order to support children with disabilities and their caregivers. Service providers also need to shift their attitudes to provide more welcoming and inclusive environments, she added.

Overall, the report largely told us what many of us suspect already: South Africa’s children are in trouble. Jamieson summed it up: “This calls for a multisectoral plan of action to address the many forms of deprivation and exclusion that children experience.” The question is whether – being largely unable to speak for themselves – they will get it. DM

* Child-headed households have decreased in the interim

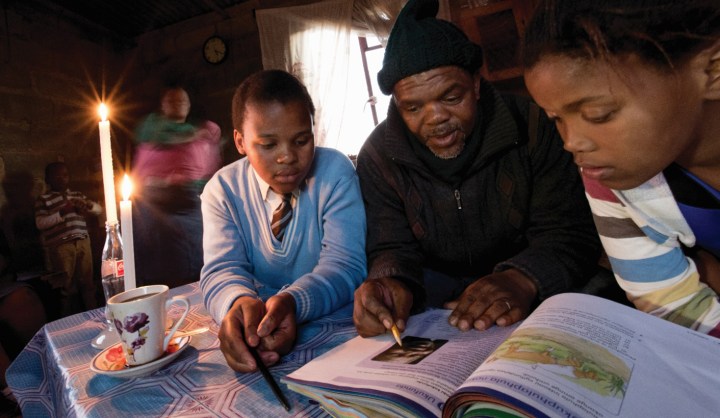

Photo: Supplied by Unicef

Become an Insider

Become an Insider