South Africa

Book Extract: Front-line feminism in the twenty-first century

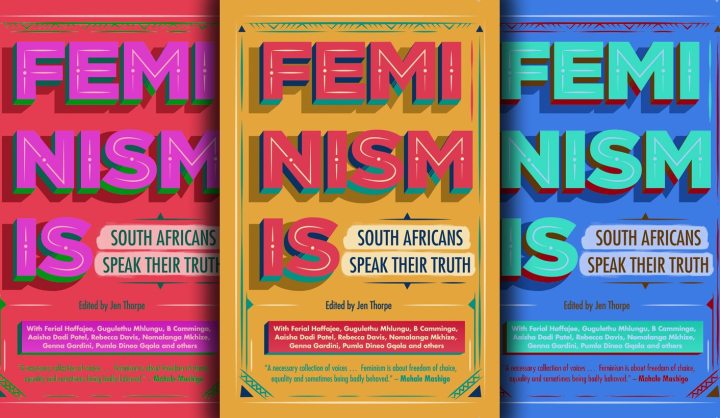

In a chapter of a new book, Feminism Is: South Africans Speak their Truth (Kwela Books), LARISSA KLAZINGA tackles what she terms front-line feminism by examining the rise of Jacob Zuma.

Feminism in the twenty-first century is not for the faint of heart: it’s a blood sport, and to survive you need a tribe you’d take a bullet for to have your back. Solitary keyboard feminism has its place in the ivory towers of the world, but over the past decade, anti-gender-based-violence activists have evolved a living, breathing front-line feminism characterised by fierce women meeting the worst of state patriarchy head-on together.

To really understand the rise of what I’d call ‘front-line feminism’, let us examine the rise of Jacob Zuma, and unpack the feminist resistance to his ascendance and the reactionary tide that helped him retain power.

The Zuma odyssey began during the then-Deputy President’s rape trial in 2006. The One in Nine Campaign was formed to support the complainant Fezeka Kuzwayo against the thuggery of the African National Congress (ANC), bent on backing-up its hyper-masculine, paleo-traditionalist leader. As the trial commenced, a small group of activists, mostly friends, mostly queer, took up position across the road from thousands of vocal, violent Zuma supporters. Over the following months, that small band of purple-clad women held the line, ensuring that Fezeka knew she wasn’t alone. That simple courageous solidarity birthed a movement of young activists who knew the stakes and joined the battle anyway.

Despite writing in a different context and era, Robin Morgan wasn’t wrong back in 1970 when she said ‘sisterhood is powerful’ (in Sisterhood is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women’s Liberation Movement). A decade after the first One in Nine Campaign protest in Johannesburg in 2006, through old-fashioned consciousness-raising, education, and radical direct action typified by the Silent Protest78 at Rhodes University and the #RUReferenceList protests, a new generation of South African feminist leaders was forged. This activism was profoundly personal, intrinsically confrontational, and based on the simple principle that solidarity with women who speak out is a game-changer.

Solidarity sounds simple: it sounds easy, and peacenik, and entirely uncontroversial. Nothing could be further from the truth. Solidarity is a radical act that confronts patriarchy’s most fundamental tenet – that women are untrustworthy; they lie, they ask for it, and when they get it, they deserve it. Solidarity is love as a political act, and it disrupts and enrages those it opposes precisely because it exposes rape as a systematic tool of oppression.

Solidarity in the context of media’s insistence that rape and incest continue to be exceptionalised becomes an act of resistance. As the media ignores most violence against women as unnewsworthy, with only the most brutal or high-profile cases making headlines, a movement based on standing with women who speak out disrupts the status quo. When the media sensationalises high-profile cases, reinforcing the myth that all rapists are monstrous violent strangers, solidarity with millions of survivors speaking out in a myriad of contexts, both public and private, is both transgressive and transformative, binding survivors and those that bear witness together.

Over the past decade, standing with survivors – believing women when we speak our truth, and creating safe spaces for women to share our violation and recovery – has created a community of people who know that violence and oppression reside in the family and in our circles of friends, and is often perpetrated by people we trust and admire.

The feminism born out of this intimate knowledge of betrayal and violence is fierce, angry, and unapologetic. It is confrontational and emotional rather than polite and reasoned, because this kind of radical solidarity comes at a cost: every survivor story you hear stays with you, haunts you, reminds you of your own violation as it forces you to hear and hold the pain of survivors, not as bland statistics, but one at a time, face-to-face.

All feminist activism is exhausting, messy work. Anti-gender-based violence activism in recent times has been downright shattering. Being confronted by the realities of patriarchy and battering oneself against its ramparts has left us all shell-shocked and broken. Feminism on the front lines looks different from the academic feminism that critiques it. We are war veterans, battling post-traumatic stress disorder, looking around, trying to fathom how ‘normal’ people go about their lives, oblivious to the war raging around them, unaware of, or unaffected by the bloodbath under way in their communities.

I’m asked all the time why I’m so angry, so combative and short-tempered, why I can’t just ‘lighten up’ and be less confrontational.

How do I explain that this is me keeping my rage in check? This is me with the lid screwed on so tight that my head hurts. I can’t breathe, I can’t sleep, and I find it hard not to lash out and burn things to the ground. I want to incite riots, and blow up buildings, and bomb the rapist overlords back to the Stone Age. I want castrations and evisceration; I want my own ‘Umshini wam’ … This is what front-line feminism feels like. It feels like war. It feels like losing. The casualties on our side number in the millions.

I listen to the critique meted out to feminist activists and politicians, and I can’t help but recognise myself in the (nasty) women around me. We are not nice. We don’t get along, and often we don’t much like each other. We don’t have much in common, but we are family, comrades-in-arms, thrown together by a passion for justice and freedom – and because our pain, trauma, and betrayal will not allow us to sit on the sidelines. To quote my favourite fictional character, Terry Pratchett’s Granny Weather-wax: ‘good ain’t nice’.

Ten years after the trial that destroyed her life, Fezeka lost her battle with HIV. As activists gathered to bury her, we could not help but reflect on how she died and how she lived. Fezeka was a feminist warrior. She struggled for justice her entire life. She stood up against one of the most powerful men on the continent out of love as much as courage. As a child of the liberation struggle, she understood sacrifice. She stood up for us, to prove that it was possible, knowing full well the cost. She was vilified, violated, exiled, abandoned, and abused. She died of her wounds. Patriarchy killed her. The liberation movement that birthed her, killed her. The man who should have nurtured her, killed her – and as a nation, we watched.

As we stood in the heat of a humid Durban springtime, we knew we were burying a struggle hero. She deserved a national day of mourning, flags flying at half-mast, the blowing of trumpets and the rending of shirts. Instead, the city streets were cordoned off for a ‘Hands off the rapist’ rally, and party hacks declared ‘we love this man’.

She died for us: broken, flawed, but loved. Fezeka was so much more than what was done to her by rapacious violent men. Comrades reminded each other of her laughter, her love of music and dancing, her warmth and kindness, her ability to teach and bring people together.

Fezeka reminded us that feminism is a verb as well as a noun.

For those of us on the frontlines, feminism is the daily grind of our lives. We are challenged to find hope to keep building a movement while holding back a tide of despair and rage. At Fezeka’s funeral, we struggled for composure, holding back violent words and calls to arms. We held each other up as we buried our dead. And then we looked to the future and started planning our next move, strategising a way forward, because that’s what feminists do. DM

Larissa Klazinga is a radical feminist and a proud nasty woman. She served on the One in Nine Campaign national steering committee, formed in 2006 to support Fezeka Kuzwayo after she filed rape charges against Jacob Zuma.

This is an extract from Feminism is: South Africans Speak their Truth (Kwela Books). The book, edited by Jen Thorpe, is a collection of contemporary feminist writing from South Africans.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider