World

I Have Been to the Mountain Top: Martin Luther King Jr, 50 Years Gone – A Personal Memory

The 50th anniversary of the martyrdom of Martin Luther King by an assassin’s bullet is narked on 4 April 2018. J. BROOKS SPECTOR contemplates the meaning of his final sermon and remembers his own moments of engaging with the aftermath of that death.

“Then Moses climbed Mount Nebo… There the Lord showed him the whole land… Then the Lord said to him, ‘This is the land I promised on oath to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob… I will let you see it with your eyes, but you will not cross over into it.’ ”

— Deuteronomy 34:1–4

In early April 1968, now 39 years old, Martin Luther King Jr seems to have reached a low point in his decades of social activism. The above-the-fold glory days of his 1965 Nobel Peace Prize, the famous 1963 March on Washington, the victories of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act in 1964 and ‘65, along with his attendance at signing ceremonies in the White House, were now years earlier.

Even further back along his trajectory, there had been theology studies in Boston, early but incandescent sermons in the family church, Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia, the civil rights marches in the southern states, the segregationist forces beating the demonstrators halfway to kingdom come amid growing global opprobrium, and then his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” and the “I Have a Dream” speech from his rich rhetorical well.

But now he was in Memphis, Tennessee, supporting a local strike by municipal garbage workers. This was clearly not an especially glamorous effort, even if it was crucial for the striking workers.

But now there were many other things weighing on his mind as well. He was increasingly aware of comments by younger black activists that his era had passed and that he should step aside. Going forward, the real leaders of black America should be more strident, more vociferous, more aggressive – they should be the leaders of groups like the Black Panthers and SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Co-ordinating Committee), and perhaps even the Nation of Islam.

King was also aware the FBI had been wiretapping his telephone conversations (and perhaps reading his mail), especially in the wake of his increasingly anti-Vietnam War message and his call for massive economic and social change – a cry to be taken up with a vengeance in the soon-to-take-place Poor People’s March on Washington in May. And he knew the FBI might even leak deeply damaging information about his marital infidelities.

Moreover, he was receiving daily death threats by phone and through the mail. Who knew which threats were terrifyingly real, versus the bizarre but relatively meaningless ones from obviously disturbed individuals? All this doubtless weighed on his mind as he thought about the grave damage such things would cause to his family.

As it happened, then, his speech to those Memphis garbage workers, on 3 April, became the final public statement of his soon-to-be cut short life. On that occasion, Martin Luther King told his audience,

“Something is happening in our world. The masses of people are rising up. And wherever they are assembled today, whether they are in Johannesburg, South Africa; Nairobi, Kenya; Accra, Ghana; New York City; Atlanta, Georgia; Jackson, Mississippi; or Memphis, Tennessee – the cry is always the same: ‘We want to be free.’ ”

For King, whatever struggle he was engaged in was not simply about the place where he was at the time he spoke. There were universal fundamentals of human dignity and purpose to be clarified for his audiences.

On this occasion, drawing upon years of theological and philosophical study and training, ranging from the thoughts of Thoreau to Gandhi and on to Reinhold Niebuhr (among others), he produced a sermon on the nature of disciplined action and sacrifice in the advancement of liberty and human dignity. Or, as he insisted,

“It is no longer a choice between violence and nonviolence in this world; it’s nonviolence or nonexistence.”

He gave this audience of rubbish collectors a recapitulation of the successes and history of the civil rights struggle through its employment of non-violence and disciplined action in the face of oppressors across the South. And he rooted this message in the idea that this struggle had not simply been about ending segregation, or gaining the vote. Instead, it was also about the broader spheres of social and economic equality – and the power of economic pressure to alter an unjust system – to bend that arch of justice, as he had liked to say.

Building to the peroration of what became his final speech, King argued for an unselfish commitment to causes such as the one in Memphis, among many others. To bring home his message, he drew upon both those ultra-familiar biblical lessons and, more personally, a near-death experience when he had been stabbed at a book signing event.

And then he ended his remarks with the text’s most famous moment, almost as if he had received a premonition of the imminent end of his life. Drawing upon the Old Testament story of Moses and the mountaintop, near the Promised Land, when the journey out of Egypt was nearly over, telling his listeners,

“Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop.

“And I don’t mind.

“Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!… Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!”

And then, of course, the next day, on the balcony of the motel in Memphis where he was staying, standing there with close aides and supporters, looking out over the streets of the city, James Earl Ray’s rifle shots rang out. And things were never the same thereafter.

News of the fatal shooting travelled swiftly across the nation. In Washington, DC, a city most people believed immune from the kind of racial rioting that had so roiled Gary, Cleveland, Chicago, or Los Angeles, whole streets were soon ablaze with burning, looting and pitched fighting against the police. From the highest point at my own university just outside that city, one could already discern the rising columns of smoke from fires that were beginning to be set alight.

Describing those events a half-century later, The Washington Post wrote,

“Then, shortly after 8 p.m., word reached the District that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. had been slain in Memphis. His assassination ignited an explosion of rioting, looting and burning that stunned Washington and would leave many neighbourhoods in ruins for 30 years.”

Fire-fighters struggled to control the resulting blazes, police fired round after round of tear gas at crowds. People began to perish in the chaos.

The paper added,

“By 2 a.m. Friday, hundreds of police had begun to regain control, but fires ignited again by noon and the riots intensified. The city’s mayor asked for federal troops to move in. Other neighbourhoods erupted — Seventh Street NW almost down to the Mall; H Street NE to Benning Road; Rhode Island Avenue NE; streets in Anacostia, among others. Stores were smashed and looted; hundreds of fires finished the job. Many never reopened…. ‘There was a confluence of anger and hurt’ about King’s death, said Charlene Drew Jarvis, a former D.C. councilwoman. ‘A lot of it had to do with, “We’ve been contained here. We’re angry about this. We owe nothing to people who have confined us.” ’ ”

The Post, in describing what was happening, noted,

“From the air, through the haze of smoke, the city looked like a battlefield. On April 5, a convoy of soldiers from Fort Myer in Virginia began rolling over Memorial Bridge into the city. More came in from Fort Meade in Maryland. Eventually, 13,000 troops would arrive — the most to occupy an American city since the Civil War.”

And here was where my own life intersected with this rising tide of rioting, the anger, and the disturbances. For some now inexplicable reason, together with three fellow members of our university’s debate team, we drove downtown on the Saturday afternoon to attend the closing ceremony and dinner for a big national university debate and public speaking competition that had taken place in a hotel one block from the White House. By the time that dinner was to take place, the White House, the Capitol Building and various other key public buildings had real military units stationed around them, with soldiers wearing camouflage uniforms on guard behind sandbags, with real machine guns ready to fire on fellow citizens if necessary.

Getting to the dinner was one thing, but returning home in the night quickly became a surreal experience. As we slowly drove up 16th Street from the White House, past famous landmark hotels, luxury apartment blocks and the fancy homes of prominent Washington residents, soldiers carrying AR-15s at port arms, stationed in the middle of the street, repeatedly stopped us.

“Identify yourselves. Where have you come from; where are you going?” they barked.

At each succeeding roadblock, our explanations seemed increasingly ridiculous, or mad. We were coming from a formal dinner in what was a near-war zone under military occupation, driving home in a typical student-owned, beaten-up, old Volkswagen, carrying four tie-and-jacket-wearing, young students, now increasingly terrified by the show of military force on a nearly empty street when it was usually one of the busiest roads of the city.

Watch: Robert F. Kennedy’s Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination Speech

A month later, at the request of a friend at another university who had been editing a politically minded student magazine, a second friend and I agreed to visit the now-encamped Poor People’s Campaign. This campaign was supposed to have been King’s next big national effort. It was going to bring together those struggles for voting rights, as well as to call for an end to overseas military adventures, along with to press for economic freedom and justice for all. The organisers were to bring thousands of people from across the nation to a temporary encampment on the Mall – comprised of tents, shacks and lean-tos to represent the conditions of the poverty stricken. Located immediately adjacent to the Smithsonian Institution’s museums and galleries, this temporary tent/shack city would showcase the continuing inequalities in the country, despite the formal end of legalised segregation. King, of course, could no longer lead it, given his death, and that role had fallen to one of his lieutenants instead.

My friend and I went to the headquarters for this effort, located quite literally at the ground zero of those fires that had swept through Washington DC during the disorders of a month earlier. It was adjacent to a whole row of burned out, still-smouldering stores, so as to get a letter of support for our naïve, even quixotic effort to report on the campaign and the encampment. But the Poor People’s campaign did not become a great success, perhaps most of all because Martin Luther King’s moral authority and oratorical ability was now absent.

Or perhaps it was also because so much of the country had become gravely tired (and sometimes greatly frightened) of riots and marches, along with those massive rallies by young people against the ongoing Vietnam War. And just a few months later, at the Democratic Party’s national convention in Chicago held to nominate the party’s 1968 presidential candidate, a veritable police riot against demonstrators took place. It was a very ugly, angry time for America. And, absent Martin Luther King’s voice and his moral stature, it became a poorer one as well.

But, looking back from this vantage point, 50 years after Martin Luther King’s assassination and the rioting that followed, the greater his stature has become in the interim. Rather than the sometimes-divisive figure that many people had still thought of him back then, especially among those who did not grasp why the country’s society had to change, the force of his moral vision has become increasingly clear and obvious in the ensuing half century.

His larger message – that freedom is not simply a matter of legalisms but is inextricably tied up with economic and social fairness and justice – is now increasingly appreciated globally, not least among most South Africans in their own Constitution.

King’s birthday has become a national holiday in America and a national monument to his memory has a prominent place on that national Mall in Washington where the March on Washington had taken place in 1963.

Watch: I have a dream – Martin Luther King

Plays have been written about his struggles with both earthly temptation and with the ideas of those who would have driven him beyond non-violence. His life has been portrayed in feature films. Global leaders quote his words, whenever a moral argument must be delivered to the political arena.

And his place in the American secular pantheon and his observation, “Let us realise the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” has become commonplace as an encapsulation of the American ideal. DM

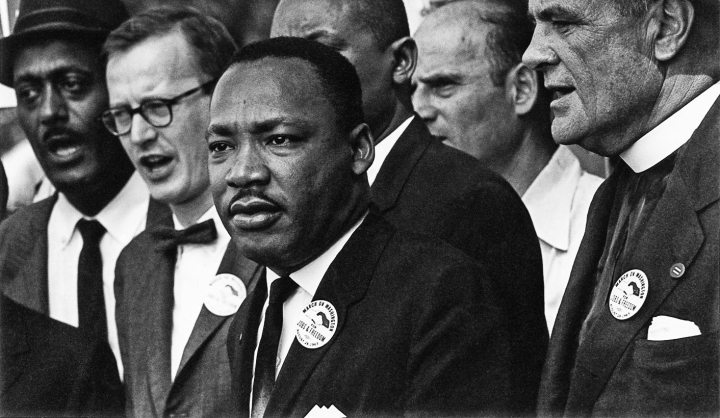

Photo: Martin Luther King at the 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. (Wikimedia Commons)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider