South Africa

Analysis: Political déjà vu – Lessons from a time of ordinary problems

One of the reasons that this political era is generally named after President Jacob Zuma is that it appears everything is tied up with him in some way or another. The rise of corruption, goes the belief, is about Zuma because he came into power already corrupt, and then that contagion spread through government. In many ways he is seen as the root cause of our situation and our problems. But, there is strong evidence to suggest that he has succeeded not just because of his political strength, but also because the very structure of our society has allowed him to. Events that occurred a full decade ago are a good illustration of this. By STEPHEN GROOTES.

In August 2007 South Africa was in a tense political situation. Two big factions of the ANC were going to war in December. There were growing cries about corruption. There were huge concerns about the abuse of power. And the then President Thabo Mbeki was an increasingly controversial figure. He was accused of neglecting the most vulnerable people in society because of his own strange beliefs. In middle-class urban areas, some people almost began to hate him. One or two people in his government appeared brave enough to defy him on the burning issue of the day. Then, on the day before Women’s Day, he fired one of them. Suddenly, and without much warning. There was controversy over how he had done it, and then a huge fight over why he had done it.

The person fired by Mbeki on that day was the Deputy Minister of Health Nozizwe Madlala-Routledge. She had become controversial because she had started to move against Mbeki’s Aids denialism, and started to work with NGOs such as the Treatment Action Campaign. It’s important to remember, in these days when we wonder why someone like Bathabile Dlamini or Mosebenzi Zwane is protected when Pravin Gordhan is not, who the most controversial figure in our politics was at that time. Then Health Minister, Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, created turmoil wherever she went, peddling her mixtures of garlic, vitamins and “nutrition”. She was accused of leaving a trail of people in her wake who were dying, despite the fact that the country could have afforded to save them.

But instead of Tshabalala-Msimang, it was Madlala-Routledge who was fired. And like Gordhan this year, she received adulation from the urban middle-class, and was hailed as a hero. Civil society groups condemned her sacking, Cosatu sharply criticised it, and she went on to be given public platforms to state her case.

The story of when she was fired will depend on your memories of the event. She made the point in an interview this week on the Midday Report that she believes the “statement of reasons for my firing were different from what he (Mbeki) had told me personally … and there were some similarities to how the former Minister of Finance Pravin Gordhan and Mcebisi Jonas were fired … in the same way there is now a lack of clarity and honesty from the person holding the highest office in the country”.

There is a bit of a factual dispute over what exactly happened. Mbeki’s spokesperson, Mukoni Ratshitanga, who was his spokesperson at the time, has given his own recollection of what happened. Interestingly, he does not quibble with the reasons she was given, but merely with the timeline of events. He suggests that she was deliberately unavailable to accept her dismissal letter. But he does not go into whether she was fired for not following the proper procedures when going on a foreign trip (oh, how innocent we were then…), or whether it was for a trip to the Mount Frere Hospital in the Eastern Cape, or whether it was in fact the most likely explanation, which was that Tshabalala-Msimang wanted her gone (In the days after her dismissal Madlala-Routledge spoke of how Tshabalala-Msimang had said to her, “I’ll fix you”. And in the days before she was dismissed, Madlala-Routledge told this reporter to watch the story around her very closely, which was probably a forewarning of what was going to occur).

Factual disputes aside (Mbeki likes nothing more than to disagree with the historical record), the resonances of her experience and those of our current situation a decade later are very clear. Again, we have the ANC divided ahead of a big conference, with a hugely controversial president who acts against someone that many people believe is the real hero.

But the real dynamic is that despite the strength of feeling on the issue, there is no way to rein in the President who is acting in this way. There is no accountability. And it would mean then that the chances of our system, and certainly the ANC’s system (but another party system could create this as well) creating this situation again, in about 10 years time, is highly likely.

Madlala-Routledge herself puts it like this, “There is a cycle in the issue around how our democracy is playing out. A party chooses who is going to be President and then refuses to withdraw the person despite very strong opposition from voters.” She goes on, “The most important things is to look into the issue of internal party democracy… at the moment we see a situation where people with integrity are thrown into the situation of a moral dilemma.” Madlala-Routledge was speaking this week in the hours before the Confidence Motion vote on Zuma, and it’s obvious which dilemma she was referring to.

There are others who have spotted the same thing. Wits Vice-Chancellor Professor Adam Habib was perhaps the first to explain the kind of déjà vu that we are feeling, and to ask how can we stop ourselves from feeling this all over again in 10 years time.

We are not the first democracy to grapple with a lack of accountability by the person who heads government. Anyone who was politically aware during the situation in Britain in the run-up to the US invasion of Iraq will see similarities to this situation. Then, Prime Minister Tony Blair was in almost complete control of the Labour Party. And despite some of the biggest ever protests seen in that country, he was able to take into a war in Iraq. To be fair, both Mbeki and Blair could not be accused of being corrupt in the sense of taking money for themselves, while Zuma is not immune from the same accusation. Britain, of course, has avoided creating a cycle as we have, Theresa May is hardly in a position to do something unpopular at the moment.

What Mbeki, Blair and Zuma have had in common is the certainty that they would not lose an election despite the criticism of their actions. It is the classic problem of power corrupts, absolute power corrupts absolutely. This would suggest that the only way to stop this from happening in our system is to make sure that the person in power is very, very scared of losing it. Considering that there are signs of a possible hung parliament or a coalition in 2019, perhaps the cycle is not in fact endless.

But this is by no means certain. The very structure of our political system, in which party bosses can basically force MPs to vote their way in Parliament, will always provide some form of protection for a leader who wants to remain unaccountable. In the end, this is possibly the real root of the problem. This would mean the only way in our system to keep them accountable would be to create a situation where a few smallish parties are key to any coalition, and can withdraw their support whenever a leader behaves in an unaccountable fashion. Imagine if, this week, parties like the UDM or the NFP had been in a coalition with the ANC and were able to vote to remove Zuma. But unfortunately, this is also a sure-fire route to instability; governments would fall with boring regularity, and they would be unable to govern effectively.

It is becoming clearer that we are in a situation where political space has been opened up, there is no one in charge in the way that Mbeki once was and Zuma was earlier in his presidency. This means that there is a small chance to try to work some change into our system. But, it is a huge challenge, you would have to tinker with something pretty fundamental to our 1994 non-revolution, the system of proportional representation. Or, the parties themselves need to reform, and introduce a system that enforces more accountability from their leaders. It gets back to one of the basic points of our current situation – Zuma is the ANC’s problem, it is up to the ANC to remove him.

It appears unlikely that any major change can be made to our system of government at the moment. Which means that either voters have to ensure that no one has too much power, or parties themselves need to reform. The alternative is that in the week of Women’s Day 2027, you will have to read this opinion piece again. DM

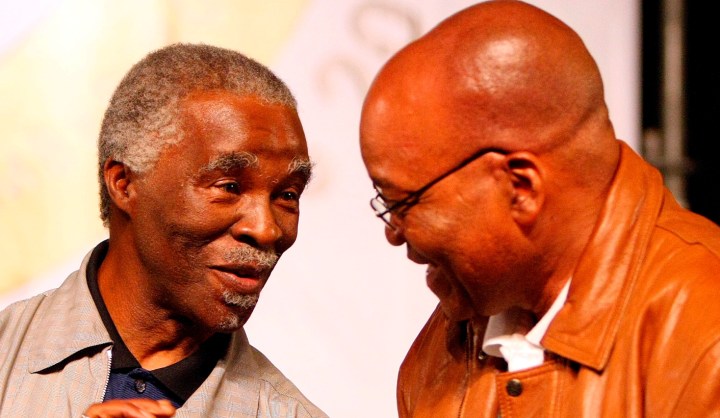

Photo: Then-President Thabo Mbeki congratulates newly-elected African National Congress (ANC) president Jacob Zuma on the third day of the 52nd ANC National Conference at the University of Limpopo in Polokwane, South Africa, 18 December 2007. Photo: JON HRUSA (EPA)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider