World

Letter from Trumpland: Unorthodox Indians in coal country

No matter who occupies the White House, we will continue to trade human gestures – stories, prayers, and conversations – as much as coal, clothes, or steel. By GLEN RETIEF.

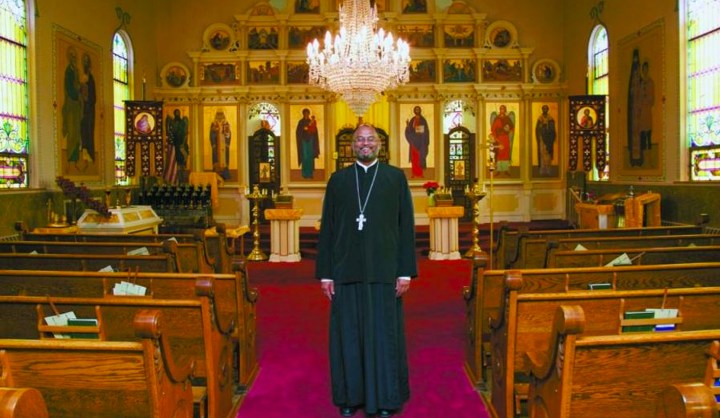

US President Donald Trump may have recently signed an executive order discouraging the Internal Revenue Service from aggressive enforcement of the Johnson Amendment, which prohibits tax-exempt religious institutions from endorsing political candidates. Yet Father John Edward, of St Michael’s Orthodox Church in Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania, will not be talking politics with his parishioners any time soon.

“It isn’t appropriate for clergy to preach narrow partisanship,” he explains.

Father John Edward is Malaysian, of Indian descent. His wife hails from India; his brown-skinned young adult son and two teenage daughters would not look out of place shopping at Durban’s Victoria Street Market or in the clothing stores of Athlone.

Edward grew up Anglican. After a winding spiritual journey, including a degree in early church history at Princeton, he decided to “go back to the roots, the cradle of Christianity” and become an American (Eastern) Orthodox priest. His first placement was here, in the hard, black anthracite heart of US coal country.

In the 2010 census, 3,129 people reported living in Mount Carmel, a mountain settlement of steep streets, white clapboard houses, and onion-domed Eastern churches. Only 30 of these self-classified as anything other than white.

So at first the Edward family felt like lone dark dots.

“After the election, one of my daughter’s schoolmates asked her when we were going to move back to India,” laughs Edward. “But now we feel accepted.”

As recently as the 1950s, coal heated most houses in the Northeastern US. It powered the economy. The consequent prosperity supported local shops, restaurants, theatres, and movie houses, as well as steel mills and factories.

Today, much as in western Mpumalanga, the land and people bear the scars. Soot stains mar house sidings and sidewalks. Mountaintops have been blasted into coal piles. In neighbouring Centralia, one of the world’s largest coal seam fires leaks smoke out of the earth.

Asthma rates in northeastern coal country are the highest in the state. Climate change, fuelled largely by coal use in the developing world, recently helped prompt the Pennsylvania government to build a $15-million flood wall along the Shamokin Creek that runs through Mount Carmel.

Medupi, the world’s fourth largest coal power station, is slated to go online in March 2018, which will probably generate further demand in places like eMalahleni and Lephalale.

But here in Mount Carmel, most of the mines have closed down as natural gas and renewables crowd out coal’s market share in North America.

Outside Father John’s church, unemployed youths smoke next to boarded up shop windows. By far the largest and most prominent building on the way into town is the sprawling, wooden red Swiss-villa-style Addiction Help Centre. Last Monday, a 27-year-old man in neighbouring Kulpmont died of a heroin overdose. Two days later another 21-year-old overdosed in his Oak Street home.

“I don’t mind when young people leave,” says Julie, a member of St Michael’s. “I’m much more worried about the ones who stay here who have nothing to do and who feel empty, lonely, and desperate.”

As in France and Britain, “job-stealing” immigrants make an easy scapegoat here for economic decline. So does globalisation itself — including competition from lower-wage countries with weak currencies, like South Africa.

One of the fiercest supporters of Trump’s border wall is Lou Barletta, Mount Carmel’s Congressman (and my own, in nearby Sunbury). Lou, as he’s known, got his political start as mayor of Hazleton, about an hour away, crafting a local ordinance penalising employers for hiring undocumented workers.

In Northumberland Country, Trump received 70% of the vote, more than any Republican in living memory. This was largely on the strength of his anti-immigrant and anti-trade rhetoric.

Given all this, one might well expect Father John Edward – a robe-wearing, brown-skinned, Princeton-educated priest whose previous family residence was within view of the Empire State Building — to be more a political and rhetorical target.

Yet when I recently attended first a Sunday Divine Liturgy service at St Michaels, and then evening prayers at the Serenity Gardens Assisted Living Home in neighbouring Kulpmont, I was struck not just by how welcomed he seemed by his congregants and the community in general, but also how badly needed.

At the Saturday vespers service, about 30 elderly people with wheelchairs and walkers listened to Edward – supported from the sidelines by his wife, Suja, and daughter, Sophia – share his evocative Orthodox chants.

One attendee wore a Navy sweatshirt. Another wore a US Marines cap, accompanied by a breathing tube. We all nodded together as we prayed for world unity.

A woman in her nineties woke up when Father John preached a sermon for Mother’s Day, telling them God knew, and appreciated, the sacrifices they’d made as parents. Although Edward did not say this, these were, of course, the same children who have mostly left for San Francisco, Austin, or Atlanta, to find work.

“God never stops loving you,” Edward told them.

He beamed, hugged several women, smiled at the man in the Marines baseball cap. Suja and Sofia distributed cookies and pastries. It was difficult, at that moment, not to see the whole Edward clan as adoptive children in this community, visiting and caring for the town’s parents.

On the one hand, the idea of darker-skinned people taking emotional and physical care of white people who express a general dislike for people of their cultural background will not seem unfamiliar to South Africans.

Yet Edward also occupies a leadership role in Mount Carmel. He persuaded his parish council to channel more support into coal country social services —food programmes, addiction treatment.

The fact of an Indian priest in a historically Russian religious tradition, ministering to Trump supporters, seems to insist that even here in one of the most conservative parts of America, cultural identities can be complex.

As for the sense of unspoken family between these young Indians and ageing white Americans: that, at least to this observer, seems to speak to a deeper, unbreakable human interdependence. How, as Mandela once put it, our compassion binds us to one another, as human beings who have learned to turn our suffering into hope for the future. How, no matter who occupies the White House, we will continue to trade human gestures – stories, prayers, and conversations – as much as coal, clothes, or steel. DM

Photo: Father John Edward, of St Michael’s Orthodox Church in Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania. Photo by Julie Hagenbuch, Journey to Orthodoxy.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider